In this episode of Crossing Cultures, we explore two iconic garden models - a grand French masterpiece and a tranquil Chinese oasis - to discover how nature and design reflect the cultural identities that shaped them.

They are places of beauty that inspire creativity and passion, but can our gardens also reveal something deeper about who we are? The French formal garden and classical Chinese garden represent two distinct approaches to landscape design, each shaped by unique cultural and philosophical roots.

Control over nature

Symmetry, precision, and grandeur epitomise the French garden style, which reached its height during the 17th century thanks to the creative genius of André Le Nôtre. Widely considered the father of formal French garden design, Le Nôtre’s first private commission was Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte.

When he arrived at Vaux-le-Vicomte, “he brought together all his genius and expertise to create the grammar of the French garden,” explains the château’s co-owner, Alexandre de Vogüé.

Vaux-le-Vicomte was commissioned in 1656 by Nicolas Fouquet, France’s then fabulously rich and powerful finance minister. Fouquet enlisted Le Nôtre, architect Louis Le Vau, and interior decorator Charles Le Brun to bring his vision to life.

“Nicolas Fouquet gathered the three finest artists at that time… telling them, you can do what you want, but there are two conditions: you must be the most daring and revolutionary in what you imagine and you're going to work hand in hand, together,” de Vogüé says.

The result was a garden defined by a central axis that ran from the château to the horizon.

"For me, the best definition [of a formal French garden] is the development of the house and garden together. One is not possible without the other, and this is wonderfully illustrated here at Vaux-le-Vicomte,” insists de Vogüé.

A Tragic End

But the story of Vaux-le-Vicomte isn’t just one of artistic triumph - it also reveals the cost of ambition. In August 1661, Fouquet hosted a lavish celebration attended by King Louis XIV to mark the garden's completion. But weeks later, the finance minister was arrested, accused of embezzlement, and imprisoned for life.

“Thanks to Vaux-le-Vicomte, [Fouquet] showed the whole of France his taste, his power, and his fortune,” says de Vogüé.

For Louis XIV, this ostentatious display was both a challenge and an opportunity.

“The king was truly inspired by this, going on to do the same thing, taking the same artists, to build Versailles ten times bigger and show the whole world, 'I'm the boss, and you don't mess with the boss'," de Vogüé reflects.

Chinese Gardens: Harmony with Nature

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, Chinese classical gardens were striving for harmony rather than control. In Suzhou, the bureaucratic heart of imperial China, gardens like the Humble Administrator’s Garden embodied this philosophy.

Modesty, rather than grandeur, defines the entrances to Suzhou’s private gardens.

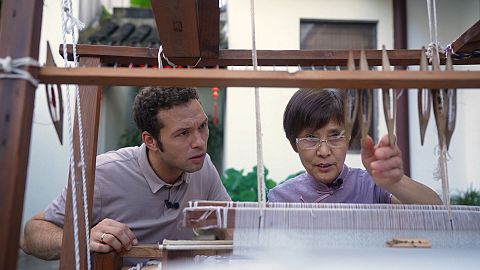

“Owners often wanted to conceal their gardens, creating an oasis of beauty hidden amid the city’s bustle,” says landscape designer Zhou Anyi.

In these spaces, water, rocks, and carefully selected plants and structures evoke the poetic beauty of China's mountains and rivers. The Humble Administrator’s Garden, created in the 16th century by Wang Xianchen, is a perfect example of the desire to retreat from worldly concerns and achieve inner peace.

“In a limited space, people strive to create their idealised view of nature,” Zhou explains. Balance and asymmetry replace symmetry and order, inviting visitors to reflect and wander through a harmonious world.

Cultural Connections

Despite clear differences, the great gardens of France and China do share some key similarities. The most striking is the use of water, which plays a defining role in both styles.

At Vaux-le-Vicomte, fountains and water features accentuate the precision and grandeur of the design. “Water is a crucial element in a French garden because it enhances the main axes and the depth of the garden,” says Luc Renault, Vaux-le-Vicomte’s fountain engineer.

In China, water flows naturally, shaping ponds and streams that extend the garden's space and integrate the surrounding scenery. “This creates fluidity and an immersive experience,” Zhou notes, allowing visitors to feel part of the landscape.

A final thought

With its structured lines and grand ambition, the French garden showcases humanity's brilliance in shaping the environment to reflect its vision. In contrast, the Chinese garden invites us to embrace nature as a partner, embodying a centuries-old philosophy of balance and harmony.

Together, these styles reveal two equally valuable perspectives: the ingenuity to transform our surroundings and the wisdom to live in harmony with them. Both approaches offer timeless lessons as we consider our evolving relationship with the natural world.